Open data, design, & development at the Office of Natural Resources Revenue

Open data, design, & development at the Office of Natural Resources Revenue

Making tough content choices

May 16, 2019

Over the years, I’ve found the discipline of content strategy to be…malleable. Sure, there are principles that guide the overarching approach, but the day-to-day mechanics of the job are shaped by the organization’s culture, its mission, the composition of the team, and the history and trajectory of the product itself, among other variables.

Common to every content strategy I’ve developed is an unavoidable reality: we must make tough content choices.

A brief history

Natural Resources Revenue Data was originally built by 18F to support the United States’ participation in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). The site served as an interactive version of the EITI annual report, required by member countries of EITI.

In practice, here’s what that meant for the site’s content strategy:

- The EITI standard mandates the formation of a multi-stakeholder group to define how EITI will work in the respective country. For the U.S., that meant, in part, that the multi-stakeholder group performed the content governance role for the site.

- The standard requires that each member country supply an independent administrator, a non-governmental entity to help coordinate the implementation of the standard. In our case, it was an outside contractor, the staff for which also developed much of the site’s content.

- The scope of data and content under EITI went beyond the federal government’s management and regulatory authority over extractive industries and included data and content related to the economic impact of the extractives sector on local economies and Gross Domestic Product.

Basically, The EITI standard provided the scope, vision, and governance for the site.

A new reality

In late 2017, the U.S. withdrew from EITI. The site would live on, but the content strategy would need to change.

Meanwhile, 18F was transitioning the work to our team. We no longer had our governance structure, outside content creators, the developers who built the site, or the EITI standard.

So what now? 😟

Making tough content choices

Our problem was a common one: we needed to define our new constraints and evaluate user needs (and our ability to meet them) within those constraints.

We started by reframing the product vision.

Defining our constraints

I didn’t fully realize at the time how important our product framing would be later on. It can be difficult to allocate the time to do this critical, illuminating work when you’re trying to onboard a new team and continue to ship features. But without it, each decision becomes more difficult and subjective, with no North Star to navigate personal preferences, political pressures, difficult choices, or pain points.

We took a couple of weeks (a sprint) to redefine our purpose and constraints, which included several elements:

With our product framing toolkit assembled, we could now audit and evaluate content against our agreed upon constraints and aspirations.

Content auditing

I’m certain there are people out there for whom auditing content is a dream come true; I am not one of them. I do, however, cherish the role of content audits in the practice of content strategy. You simply can’t move forward with a strategic vision without taking into account the existing disposition of site content.

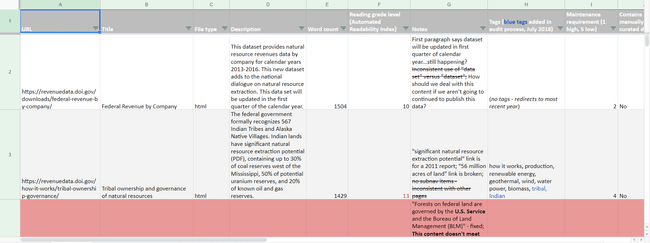

The content audit isn’t just an inventory of existing content; it endeavors to capture characteristics of the content that impact our decision making. That is, we’re not only evaluating content according to alignment with our revised product vision, but also trying to understand the previous and current governance of the content, its relative maintenance requirements, its complexity, its structure, its value to users, and so on.

A content audit will often reveal the limits of user-centered content design: your team has to be capable of delivering on the user needs you’ve identified. So that’s where we head next…

User needs are just part of the equation

Our team tries to take a holistic approach to identifying user needs. We examine analytics, we interview users, we iterate and conduct more research…our process starts and ends with users in mind.

But here’s a truth that often goes unmentioned in discussions about user-centered design: user needs are only part of the equation, albeit an integral part. Your team’s ability to deliver on user needs is an unavoidable constraint.

So how do we go about weighing user needs relative to our team’s capacity to deliver on them?

Content evaluation and prioritization

Excuse the use of the word “prioritization” here. It’s an overly artful term for which I’ve struggled to find a sufficient alternative. The point is, you can’t do everything. You have to make tough choices. Here’s an example.

In the EITI era, our site contained data and supporting content outside the scope of our revised product vision. Our data included:

- National and state GDP for the overall extractive industries sector

- Wage and salary data for the overall extractive industries sector

- Case studies for counties with significant economic reliance on extractive industries

- National extractive industries production from all land categories (private, state, and federal)

While this data was and is available elsewhere (we pulled it in from other government agencies), our analytics showed some users were accessing it on our site. It no longer aligned with our product vision, but it had at least some value to some users, and it provided context for our “core” data.

Since it didn’t neatly align with our product vision, but still had demonstrable user value, I wanted to evaluate it further.

I developed a simple content evaluation formula to help guide these tricky content decisions, balancing three variables:

- anticipated or observed user benefit

- alignment with product vision

- anticipated or observed creation and maintenance burden

| Score range | Priority | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0–10 | low priority | Content isn’t worth the time and effort to produce or will incur too high a maintenance burden relative to its user value. |

| 10–20 | medium priority | Content might be worth the time and effort but should not be first priority. |

| 20–30 | high priority | Content is clearly worth creating and should be first priority. |

Given some of these categories are wildly subjective, I tried to attach specific, quantitative indicators for each range. For instance, for “Anticipated or observed user benefit,” I created three indicators for the 0–10 range:

- We have conducted research that demonstrates at least 80% of sampled current and/or target users would receive no benefit from the content.

- The content is available elsewhere, where it is more likely to be sought and discovered by users.

- If content already exists on the site, our analytics show zero referrals and fewer than 5% total pageviews per month.

While these indicators aren’t perfect, they do give us some parameters to evaluate the content against. And even if we don’t use the formula to evaluate every single piece of content, it still frames the way we think about our content choices. Simply documenting a process for evaluating content can impact the way a team approaches those tough content choices.

Understanding your constraints is user-centered design

There’s no question that a user-centered approach to product design is the way to go, and its introduction to the development of government digital services is a major win for the public. But it isn’t the only factor to consider.

Your ability to deliver user value is always constrained by, well, your ability to deliver user value. There are always trade-offs and edge cases. And as the composition of your team changes or your users’ needs evolve, you have to be ready to adapt.

In the end, making these tough content choices is user-centered. Having no content for a certain subject is often better for the user than having outdated, misleading, or erroneous content.

So find a formula that works for your organization, one that allows you to deliver the highest quality content for your users within your constraints.

Note : Reference in this blog to any specific commercial product, process, or service, is for the information and convenience of the public, and does not constitute endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Department of the Interior.